New research: the political language of "fairness"

Politicians have a shared language of fairness, but an analysis shows differences between who in society they believe are entitled to it.

"Taxpayers", "hard-working families" and "pensioners" are the people in society politicians most often mention and align with when they talk about who is entitled to fairness.

These are among the key findings from an analysis of the "language of fairness" I’ve written for the Fairness Foundation. The report used corpus analytics techniques to make sense of 16,000+ quotes by politicians that mentioned the word "fairness" between 1998 and 2023.

Mentions of fairness have been on on the rise and there is a “language of fairness” shared across the political spectrum.

Fairness was mentioned regularly by politicians from all parties. Unsurprisingly, the frequency of mentions by politicians from a particular party was at least partially correlated with the number of seats that party held as the table below shows.

It’s possible that fairness is a value associated with opposition, or at least a lack of political power. The analysis found evidence for an inverse relationship between fairness mentions and the number of seats held by a particular party. The table below shows a reduction in the number of fairness mentions (per seat) in the House of Commons by Conservative MPs between 2005 and 2010 as they gained more seats. By contrast, the proportion of Labour speeches that mentioned fairness rose as they lost seats.

A similar pattern holds when we look at other parties. For example Scottish National Party politicians’ mentions of fairness decreased as proportion after more SNP politicians were elected.

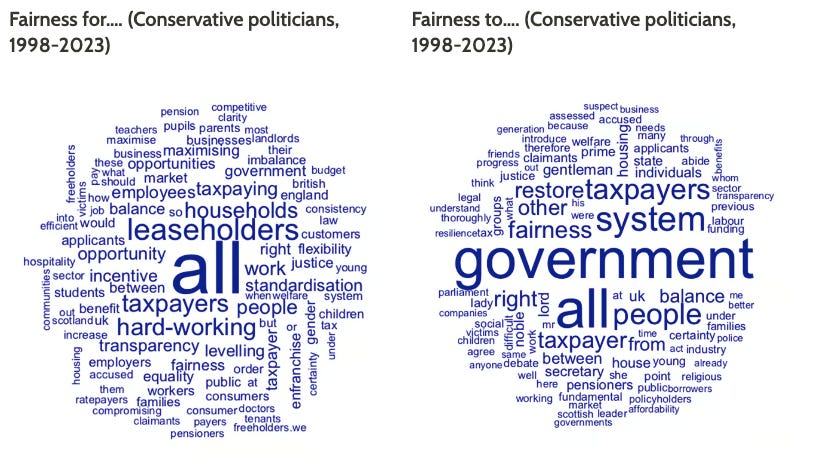

Who do politicians think is entitled to fairness?

"Taxpayers", "hard-working families" and "pensioners" were the personas in society that Conservative politicians most often mentioned when they talked about who is entitled to fairness.

It was striking just how focussed Conservative politicians were in aligning with these groups.

By contrast Labour politicians were far less precise in pointing a finger to the groups in society they believe should be entitled to fairness.

Using “fairness” to divide

Conservative politicians regularly used the language of fairness to draw lines between “in groups” and “out groups” in society.

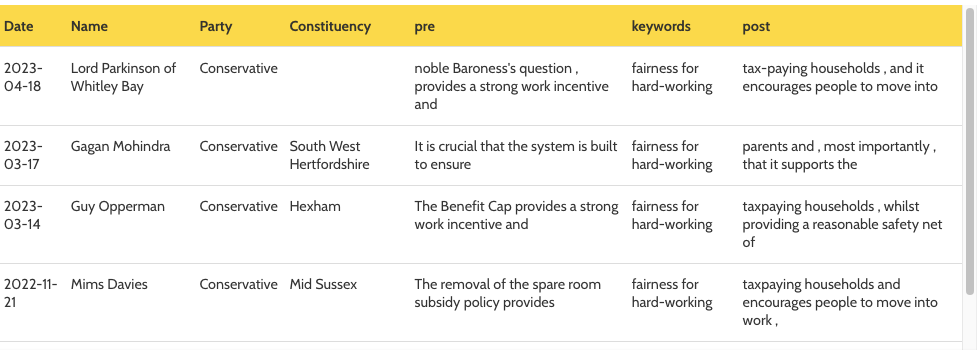

There were many examples Conservative politicians using the phrase"fairness for hard-workers" to justify policies such as the benefit cap and the “spare room subsidy” (bedroom tax). The “hard-working” frame became more popular among Conservatives in 2014, which may be connected to the introduction of the benefit cap in 2013.

At the recent Conservative Party Conference the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, leaned in to the same language of fairness to draw a line between “workers” and people seeking a “life on benefits.”

“I’m proud to live in a country where, as Churchill said, there’s a ladder everyone can climb but also a safety net below which no one falls. Paying for that safety net is a social contract that depends on fairness to those in work alongisde compassion to those who are not. Since the pandemic things have been going in the wrong direction. While companies struggle to find workers, around 100,000 people are leaving the labour force every year for a life on benefits. As part of that we will look at the way the [benefit] sanctions regime works. It is a fundamental matter of fairness.”

A tweet in response, by Labour's Shadow Secretary of State for Work and Pensions,

Liz Kendall, illustrate the difficulty that progressive minded politicians seem to have with personifying their own version of fairness.

She responded by saying:

"real opportunities matched by the responsibility to take them up, because that's what fairness is about."

In contrast to Hunt what was missing from Kendall’s rhetoric was any sense of a clear object, group or persona in society that ought to be a progressive object of fairness.

For Conservatives, the message to voters is clear: these are the groups we are aligned with. Labour voters are left to fill in the blanks for themselves.

Conclusions

More research into how politicians talk about values such as equality or freedom would be helpful in assessing their relative salience compared to fairness.

Politicians should consider whether talking about fairness in a more unifying (and united) way might be more aligned to public attitudes and might encourage better policy-making.

Understanding how politicians align around values like fairness can help campaigners to ensure they are using the right language when they engage in advocacy work.

Read the full report here

Visit my website at Campaign Salience